Exhibition: 5,000 Years of Iranian Art, Design and Culture

Epic Iran explores 5,000 years of Iranian art, design and culture, bringing together over 300 objects from ancient, Islamic and contemporary Iran. It is the UK’s first major exhibition in 90 years that present an overarching narrative of Iran from 3000 BC to the present day. The V&A organises epic Iran with the Iran Heritage Foundation in association with The Sarikhani Collection.

Iran was home to one of the great historical civilisations, yet its monumental artistic achievements remain unknown to many. Epic Iran explores this civilisation and the country’s journey into the 21st century. The exhibited works range from sculpture, ceramics and carpets, to textiles, photography and film. They reflect the country’s vibrant historical culture, architectural splendours, the abundance of myth, poetry, and tradition that have been central to Iranian identity for millennia. The evolving, self-renewing culture is evident today. The audience can see the Cyrus Cylinder and intricate illuminated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, ten-metre-long paintings of Isfahan tilework, Shirin Neshat’s powerful two-screen video installation Turbulent, and Shirin Aliabadi’s striking photograph of a young woman blowing bubblegum, among other artworks. The exhibition offers a perspective on a country often seen through a different lens in the news.

The V&A has collected the art of Iran since the museum’s founding over 150 years ago and has one of the world’s leading collections from the medieval and modern periods. Drawing on notable highlights and excellent works that haven’t been exhibited in living memory, Epic Iran features works from the V&A alongside substantial international loans and artworks from significant private collections, including The Sarikhani Collection.

Tristram Hunt, Director of the V&A, said: “Ninety years since the last major UK exhibition to cover 5,000 years of Iranian art, design and culture, Iran has undergone a total transformation, and the cultural landscape has changed dramatically. Epic Iran serves a vital purpose in enabling audiences in Britain to discover more about one of the world’s great historical civilisations and its incredible creative output in the 21stcentury. This landmark exhibition unites the ancient and Islamic study of Iran – often seen as two separate disciplines – alongside a powerful modern and contemporary section, allowing the Iranian people’s artistic achievements across millennia to be considered in their entirety.”

Epic Iran features ten sections set within an immersive design that will transport visitors to a city, complete with a gatehouse, gardens, palace, and library. Designed by Gort Scott Architects, each section has a different atmosphere, reflecting the objects displayed, time, and place in history.

About the exhibition

The first section introduces the Land of Iran with striking imagery of the country’s dramatic and varied landscapes. Iran is home to mountain ranges, searing deserts and salt pans, lush forests and various coastlines. These have shaped the country’s social, economic, and political history, and it is from this landscape, the artistic cultures covered by Epic Iran emerged over the past 5,000 years. Beginning at the dawn of history in 3200 BC, marked by the earliest known writing, Emerging Iran shows that Iran’s rich civilisation rivalled those of Egypt and Mesopotamia even before the rise of the Persian Empire. Animals and nature are a recurring motif – reflecting their importance in society at the time – with ibexes, gazelles, lions, and birds decorating pottery, cups, axe heads and gold beakers. The section also features figurines and items from everyday life, including earrings and belt fragments. The Elamites dominated south-west Iran, but from 1500 BC, Iranian-speaking people began arriving from Central Asia.

The Persian Empire spans the Achaemenid period, starting in 550 BC when Cyrus the Great was crowned king of the Medes and Persians, uniting Iran politically for the first time. With its capital Persepolis, the empire became the most extensive pre-Roman world, with a rich artistic culture. Archaeological finds reveal insights into kingship and royal power, trade and governance of society, explored in this dramatic section through stone reliefs from Persepolis, originally painted; large-scale casts with colours projected onto them; metalwork such as jewellery, coins and gold and silverware. Highlights include the Cyrus Cylinder – on loan from the British Museum – often celebrated as the first declaration of human rights, which can be misleading, and a gold armlet in the V&A collection from the Oxus Treasure. The section also features eight plaster casts from the V&A, cast from frieze panels from the Palace of Darius at Susa.

The fourth section, Last of the Ancient Empires, covers dynastic change when Alexander the Great overthrew the Persian Empire in 331 BC. The Greeks were quickly replaced by the Parthians, who the Sasanians in turn defeated. Nevertheless, 400 years of stable reign followed: Zoroastrianism became the state faith, and influential art and architecture traditions developed, with the Sasanian style enduring long beyond the dynasty’s fall. The section showcases Parthian and Sasanian sculpture, stone reliefs, gold and silverware and coins. Highlights include royal busts, such as a fifth century AD bust from The Sarikhani Collection, and a silver ewer from the Wyvern Collection, depicting women dancing.

John Curtis, co-curator of Epic Iran, said: “Visitors will be astonished by the quality and variety of objects from Ancient Iran, showing that it had a civilisation every bit as advanced and prosperous as those in neighbouring Mesopotamia and Egypt. Moreover, it is clear that the Persian Empire, founded in 550 BC, inherited a rich legacy from earlier periods of Iranian history.”

The fifth section, The Book of Kings, shows how Iran’s long history before the arrival of Islam was understood in later centuries – primarily through the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, which is the world’s greatest epic poem, completed by the poet Firdowsi around AD 1010. Combining myth, legend, and history, the Shahnameh provides a widely honoured and therefore influential version of events, rooting Iran’s long history in the minds of its people. Epic Iran features a series of elaborate illustrated manuscripts and folios depicting scenes from the Shahnameh, loaned to the exhibition from The Sarikhani Collection and British Library.

Qaran Unhorses Barman, a folio from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, about 1523–35

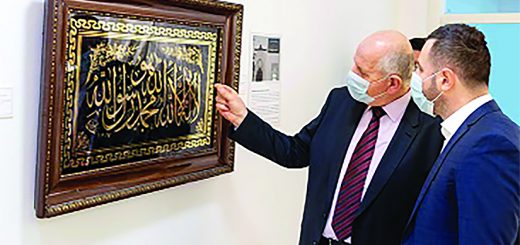

Change of Faith explores the place of Islam in Iranian culture in the millennium and more that followed the Arab conquest in the mid-seventh century AD. This section introduces the Holy Qur’an and the role of the Arabic language in Iran, which became the common language of intellectual life in the country, while the art of calligraphy in the Arabic script became highly developed and an essential element in Iranian design. The section also explores how conversion to Islam gave Iranians a new understanding of history focused on the Prophet Muhammad and his immediate successors. On loan from the Wellcome Collection, a number of exquisite Qur’ans and manuscript illuminations feature, alongside a prayer rug, a battle and parade armour, and celestial globe.

Charting the rise of Persian poetry, Literary Excellence reveals how – from the 10th century AD – Persian written in the Arabic script emerged as a literary language in the royal courts of eastern Iran. Royal patronage meant manuscripts were incredibly refined, and poetry became part of the visual arts due to poetic inscriptions, which appeared on items including ceramics, metalwork, and even carpets. For example, the V&A’s Salting Carpet includes verses by Hafiz in its border, whilst a bottle and bowl from the 12th century, decorated in lustre pigments, feature poetry in Persian. Much was also written in praise of rulers, with poetry finding its visual counterparts in art representing royal power.

Bottle and bowl in poetry in Persian, 1180-1220

Featuring rich material from the 13th century AD onwards, Royal Patronage demonstrates how Iranian traditions of kingship were reborn after Islam, with the return of royal customs like robes of honour, the creation of great art and architecture, and insight into internationalism as a two-way exchange. Recreating the splendour of Isfahan, three ten-metre-long paintings that replicate tilework patterns from the city’s domes are suspended in arcs from the ceiling to suggest a dome interior. An AV projection uses the paintings to reconstruct the appearance of the entire dome. Technical architectural drawings from the nineteenth century and a selection of tiles complement the paintings. The section looks at how Iran was influenced by the wider world – from China and Europe in particular – as is apparent, for example, from the development of blue-and-white ceramics. Important Iranian objects that have been in Britain for three centuries also feature, including the Buccleuch Sanguszko Carpet and two oil paintings loaned by Her Majesty The Queen from the Royal Collection.

The Old and the New explores how the Qajar dynasty looked back to their predecessors to legitimise their power while also seeking to modernise and scope new relationships with Europe. The introduction of photography in Iran in the mid-1800s profoundly affected the way Iranians represented themselves. Fashion also features an entire outfit, a short skirt likely influenced by European ballet tutus, and watercolour paintings of Iranian women made for tourists visiting the country. The final section looks at how Iranian artisans sought new markets for their skills in the 1880s when their new clientèle included the V&A itself.

Tim Stanley, co-curator of Epic Iran, said: “This exhibition offers a rare opportunity to look at Iran as a single civilisation over 5,000 years. Objects and expertise have come together to tell one of the world’s great stories in art, design and culture. In the Islamic period, political power in Iran was re-cast in many different forms, but an overarching sense of history and a deep devotion to Persian literature survived the turmoil of events. In 1501 the Imami form of Shi’ism became Iran’s official religion, giving the population a unifying set of beliefs that set them apart from their neighbours. Shared beliefs, memories of a glorious past and a joy in Persian poetry are still a vital part of life in Iran today.”

Bridging the 1940s to the present day, the final section Modern and Contemporary Iran, covers a period of dynamic social and political change in Iran, encompassing increased international travel and political dissent, the Islamic Revolution, the Iran-Iraq War, and the establishment of the Islamic Republic. Works by Sirak Melkonian, Parviz Tanavoli, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, and Bahman Mohasses showcase the mid-century explosion of artistic modernisms, which dramatically ended with the 1979 Revolution and Iran-Iraq War. The cultural scene flourished again in the 1990s under the mercantilism of Rafsanjani and liberalism of Khatami, and modern technology means Iranian contemporary art exists in a world without boundaries. Today, Iran has an evolving, self-renewing culture: some works are influenced by tradition, and many are experimental both in medium and expression. Epic Iran features work by Iranian artists living in Iran and based overseas, with works by artists including Farhad Moshiri, Avish Khebrehzadeh, Ali Banisadr, Shadi Ghadirian, Hossein Valamanesh, Shirin Neshat, Shirazeh Houshiary and YZ. Kami.

The modern & contemporary section of Epic Iran include works by Massoud Arabshahi, Siah Armajani, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Marcos Grigorian, Parviz Kalantari, Leyly Matine-Daftary, Sirak Melkonian, Ardeshir Mohasses, Bahman Mohasses, Behjat Sadr, Sohrab Sepehri, Parviz Tanavoli, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, Shiva Ahmadi, Azadeh Akhlaghi, Shirin Aliabadi, Ali Banisadr, Mohammed Ehsai, Shadi Ghadirian, Bita Ghezelayagh, Rokni Haerizadeh, Khosrow Hassanzadeh, Shirazeh Houshiary, Pouran Jinchi, Y.Z. Kami, Avish Khebrehzadeh, Farideh Lashai, Tala Madani, Farhad Moshiri, Shirin Neshat, Mitra Tabrizian, and Hossein Valamanesh. The exhibition will also include documentary photography by Abbas, Hengameh Golestan, Kaveh Golestan, Bahman Jalali, Rana Javadi, Mehdi Khonsari, and Malie Letrange.

Ina Sarikhani Sandmann, Associate Curator of Epic Iran, said: “Contemporary Iranian art is dynamic and exciting, critically self-examining and engaged in the global world, and both intellectual and playful. The rich variety and quality, often radical and experimental and unapologetic in playing with themes such as gender, politics and religion, may surprise visitors – and helps explain why Iran’s long legacy of culture continues to be so relevant to the world today.”

Recent Comments