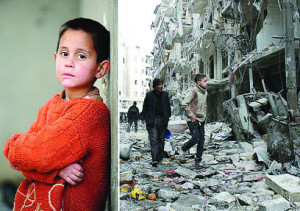

Growing Up With Violence

Emily Retter

At just three years old Gudi has grown up knowing nothing but war. He screams in his sleep – and needs time and help to forget the horrors he has seen

At just three years old Gudi has grown up knowing nothing but war. He screams in his sleep – and needs time and help to forget the horrors he has seen

Gudi is three.

He looks at me with the shyness and suspicion typical of a three-year-old weighing up a stranger.

When he smiles cheekily and scarpers, jumping over pebbles and puddles, it’s with the same carelessness of any other three-year-old.

But Gudi isn’t most three-year-olds.

He is a three-year-old Syrian refugee, which means his large brown eyes have seen blood, violence and suffering. His tiny, tanned ears have absorbed bomb blasts and death threats. His small, sweaty palms have held and pointed a gun.

His age has become symbolic.

It represents the number of years the bloody civil war in his homeland has been raging, since the uprising of rebels against Bashar al’Assad’s government regime on March 15 2011.

This has now spiralled into stalemate as infighting between disparate rebel groups stops them uniting to overthrow al’Assad, who is now receiving support from groups in countries like Iraq.

Gudi was a baby of five months old when it all began, so has known nothing but war.

“He has come face to face with al-Qaeda,” says his father, 34, who is too afraid to be named because he is wanted by the terror group.

Among the splintered rebel groups are Islamists hijacking the campaign. He rose against them in his hometown of Raqqa, and now they want to behead him.

“Al-Qaeda came to our house twice when Gudi was there. They threatened to take my wife unless I handed myself in. They said they wanted to butcher me.

“When I got home Gudi told me the military men had come, he said they were going to take his mum, he had heard it all, he was very scared.

“That night we left at 2am, under the cover of darkness. We could take very little, we had to flee.”

Speaking candidly, the father also expresses his shame that because of his involvement in the fighting, Gudi knew how to handle a gun by the age of two. He is barely able to look me in the eye.

“I was bringing weapons to our home, I needed them for my protection, for our protection.

“But my children were playing with them. I hated to see that. Gudi was pointing them, imitating firing them. He was growing up with violence in his mind.”

And he explains his son came very close to losing his life completely.

“Once a missile came through the wall of his bedroom at 5am while he and his brothers and sister were sleeping. Thankfully it didn’t explode.

“I heard the noise, rushed in and threw it outside as hard as I could. It was so hot I got burns all over my hands for a month. The children woke up crying and screaming.”

The father had little time to prepare his son for leaving his home; leaving behind the toys, games and playmates that had come to mean so much to him.

And he couldn’t prepare him for the three nights the family spent sleeping in the open air at the border between Syria and Kurdistan, northern Iraq, where 225,560 refugees have sought safety since it began to open intermittently since last August.

The family, in their haste to leave, forgot the £4,200 life savings they had stashed in their home in cushions. They only had £600 to their name – and used almost £200 to pay smugglers to bring them across the border.

There are few words he can find to explain to Gudi why they had to leave, and come to Erbil, the capital of Kurdistan, which alone has seen an intake of 84,000 Syrian refugees.

And why when they first arrived the family were forced to sleep in a shed next to 11,000 chickens, engulfed in their stench.

Now Gudi sleeps with his mother, father, two brothers and a sister, aged eight, seven and one, in one room. Next door his grandparents and uncle sleep. Next door to them another uncle, auntie and baby cousin sleeps. They live and eat in these rooms too.

They only get two hours of electricity a day. Water comes through the roof close to the tangles of wires in the corners, and at night it is freezing.

One in ten Syrian children are now refugees. Those that remain in their homeland risk death – a fate that has befallen 7,000 children there.

Gudi’s dad says: “He cries and screams in his sleep. If he hears planes or noises like shooting he wets himself and hides. He bed wets every night.”

For his third birthday in October Gudi received nothing. As normal, he played with his siblings and the other refugee kids in the rubble and litter-strewn street outside.

He does not go to nursery. He does go to a Child Friendly Space, a facility set up by Save the Children to provide some education and most importantly, safety, to refugee children.

Here he plays, takes part in art and sports. The charity aims to provide a sense of normalcy for children in the midst of crises.

It also trains staff to provide psychosocial support for children and families.

And the charity is working to provide additional learning spaces, and to extend the capacity of Arabic schools for Syrian children.

For kids Gudi’s age, up to five, early child care classes are being established, including book banks to increase literacy.

Nevertheless, his father says he worries about Gudi’s development.

“He doesn’t learn much and we are starting from scratch. In Syria he didn’t have any learning.”

Most of all though, his fear is for what is going on in three-year-old Gudi’s mind. He says little, but inside his little dark head there are dark images – sights and sounds which may need expert help to heal.

“My son needs time and help to forget all this. I fear for his future. As a father I do not know what to do.”

‘My aunt found a girl’s head in a plastic bag’

Eight-year-old Aya, fresh from Kawergosk refugee camp’s learning centre, is pretty in pink.

She skips into her family’s tent and sits quietly with her drawing books.

Inside her curly head though, are murky, deep-set fears. And what comes out of her lips is shockingly at odds with her age.

We sit around the tent and listen to what she tells us in silence. Every one of us wants to erase her brain and allow her to start again.

“Back home, my aunt found a girl’s head in a plastic bag outside her door.”

Here, she stops. Her talkative brother Sarbast, 10, fills in the unspoken.

“She is very afraid someone will do it to her. I don’t like seeing her so worried and afraid.

I want to protect her and my family.”

Their mother, Kafaa Hassan, 30, who fled to northern Iraq with them, her husband and eldest son Adam, 12, last August, explains quietly: “It was a woman of about 20, she had been beheaded, my daughter overheard us talking about this and now she talks about it like she saw it.”

Beheadings are a terrifying reality in Syria, now into its fourth year of war.

But what Aya reveals next none of us have heard before.

“I miss my best friend. But we couldn’t talk in school anymore. We were too scared. The soldiers, the secret police, listened to us and watched us. They had cameras in the classrooms and the playgrounds recording us.

“I remember once there was a child who was saying stuff against the regime and the teacher called his parents to come and get him and go before the soldiers came for them.”

The little girl, who loves basketball, suffers nightly terrors.

Her brother, although he is bolder than his sister, regaling us of stories of how he confronted checkpoint guards who stole the family’s chairs, has them too.

“The dreams and nightmares get worse, 10 days ago Aya woke up screaming so loudly and my little boy did too at the same time, they were both dreaming about a man holding a knife and running after them,” says their mum.

“Aya dreams about monsters too, we will be asleep and suddenly she comes and jumps on us.”

Aya also has an additional fear. She has seen tents on fire in Kawergosk, caused by the electric heaters inside. It happens frighteningly frequently.

“She worries our tent will burn. She is scared when I cook,” says her mum.

These children’s slim, light bodies are weighed down with more fear than most adults feel in a lifetime.

Sarbast’s solution is to draw.

He tells me how his school was bombed. Luckily the missile didn’t explode.

Over 100 schools in Damascus have been targeted like this.

He says with heartbreaking insight: “They do it to kill us kids so they can bring our parents down.”

Recent Comments