The cities that need a warning label?

Jerusalem conjures up a sense of the holy, the historical and the heavenly to a potentially overwhelming extent

Oliver McAfee was supposed to be home in time for Christmas 2017. But the 29-year-old landscape gardener, originally from Dromore in Northern Ireland’s County Down, hasn’t been seen since 21 November 2017.

McAfee had been cycling along the Israel National Trail, near the desert city of Mitzpe Ramon, before he vanished. His bicycle and tent were found two months later in the Ramon crater in the southern part of Israel. Travellers have since handed in his wallet, keys, and computer tablet discovered along the trail.

Media outlets were quick to raise the possibility of Jerusalem syndrome – a psychotic state (or a break from reality) often linked to religious experiences. Sufferers become paranoid. They see and hear things that aren’t there. They become possessed and obsessed. And sometimes, they disappear.

At the turn of the millennium, doctors from Israel’s Kfer Shaul Mental Health Centre reported seeing around 100 tourists a year with the syndrome (40 of whom needed hospital admission), most commonly Christians but also some Jews, and a smaller number of Muslims. Jerusalem syndrome was a form of psychosis, they wrote in the British Journal of Psychiatry, in a city that “conjures up a sense of the holy, the historical and the heavenly”.

Many had an existing mental health disorder, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, which had prompted them to embark on their delusional holy mission. The doctors described a US tourist with schizophrenia who began to weight-train at home and increasingly identified with the biblical character Samson. He journeyed to Israel, fixated on moving the giant stone blocks of the Wailing Wall. Intercepted by police, the man was admitted to hospital, treated with antipsychotic medications, and flown back home accompanied by his father.

But others developed psychosis in Jerusalem in the absence of a history of mental illness. It was a relatively small number – 42 of the 470 tourists admitted over 13 years – but the cases were as dramatic as they were unexpected.

Typically, these people became obsessed with cleanliness and purity soon after their arrival to the city, taking countless baths and showers and compulsively cutting their toenails and fingernails. They fashioned a white toga, often from hotel bed linen. They delivered sermons, shouted psalms and sang religious hymns on the streets or at one of the city’s holy places. This psychosis usually endured for a week or so. Occasionally, they were treated with sedatives or counselling – but the definitive cure was “physically distancing the patients from Jerusalem and its holy places”.

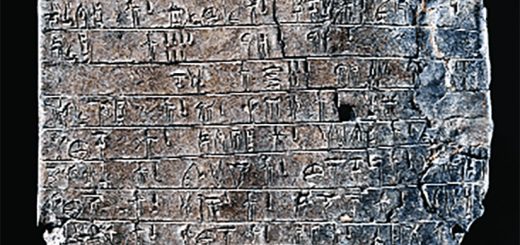

The authors suggest that these tourists (usually from “ultra-religious families’’) experience a discord between their subconscious idealistic image of Jerusalem and the concrete reality of a busy commercial city, leading to the syndrome. One writer has suggested that the city could be a “breeding ground for mass delusion”, referring to centuries of territorial disputes between faiths with resulting “friction, plots, and delusional thinking”. Indeed, Jerusalem syndrome isn’t a new-fangled affliction: descriptions suggestive of it date back to the Middle Ages.

Paris syndrome has been named for Japanese tourists who develop psychosis, seemingly crushed that Paris is not the city of their dreams

As for the possibility of Jerusalem syndrome in Oliver McAfee, this wasn’t some newfound fascination with religion on his part; he was already said to have been a devout Christian. But soon after his disappearance, his brother expressed concern about pictures from Oliver’s camera: “The nature of them is just a bit out of character and suggests he might not have been quite himself. One of them showed a lot of litter and debris around his camp and that was just not like him at all.” At a later press conference after reviewing more evidence, though, he seemed to have changed his mind, saying they’d spent “hour upon hours going through the photos, going through the journals and everything ties in with this – for Oliver this was a normal, normal trip”.

Investigators have pointed to the discovery of torn passages from the Bible weighed down with rocks where he disappeared, scriptures in his handwriting, written references he made to Jesus fasting in the desert, and according to one report, a “chapel” – an area of sand, flattened by a bicycle tool, within a circle of stones.

A Facebook page (@helpusfindollie) was established in the aftermath of his disappearance. Here’s one of the last posts: “I’ve been wondering ‘what do I say when there’s nothing to say?’ The first anniversary of Oliver’s disappearance has come and gone; and sadly, it feels as though answers are still a million miles away.”

Just as doctors in Jerusalem may be more likely to diagnose Jerusalem syndrome because they see it more often, psychiatrists in Florence encounter similar symptoms under different circumstances. It seems that visitors are so consumed by the magnificence of the city’s art and architecture that they are occasionally gripped by psychosis. One 72-year-old artist visiting Ponte Vecchio bridge became convinced within minutes that he was being monitored by international airlines and that his hotel room was bugged. A woman in her 40s believed that figures from the frescoes of the Strozzi Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria Novella were pointing at her: “It seemed to me that they were writing about me in the newspaper, they were talking about me on the radio and they were following me in the streets.”

Florentine psychiatrist Graziella Magherini described more than 100 tourists who had attended the Santa Maria Nuova hospital between 1977 and 1986 who had experienced palpitations, sweating, chest pain, dizzy spells and even hallucinations, disorientation, a feeling of alienation and loss of identity. Some had tried to destroy works of art. This was all brought on, Magherini said, by “an impressionable personality, the stress of travel and the encounter with a city like Florence haunted by ghosts of the great, death and the perspective of history”. It was just all too much, she suspected, for the sensitive tourist.

One artist visiting Florence s Ponte Vecchio bridge became convinced within minutes he was being monitored by international airlines

She named the condition Stendhal Syndrome after the French author who himself described being “absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty” and “seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart” as he emerged from the city’s Santa Croce Basilica during an 1817 visit. “The wellspring of life was dried up within me, and I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.”

Although only two or three cases of so-called Stendhal syndrome are seen annually these days, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence continues to see its fair share of emergencies. One man had a seizure as he gazed upon Botticelli’s Primavera recently and another visitor fainted by Caravaggio’s Medusa. Speaking to the Corriere Della Sera newspaper shortly after a visitor had a heart attack in front of another Botticelli (The Birth of Venus), the Uffizi’s gallery director said “I do not propose a diagnosis but I know that facing a museum like ours, so full of absolute masterpieces, certainly constitutes a possible source of emotional, psychological, and even physical stress for the effort of the visit.”

In contrast, sometimes a city doesn’t quite live up to expectations. “Paris syndrome” has been named for Japanese tourists who develop psychosis, seemingly crushed that Paris is not the city of their dreams. Distressed by the stern faces of locals and the alleged paucity of friendly shop assistants, a breakdown of sorts ensues. “In Japanese shops, the customer is king,” explained a representative from an association that helps Japanese families to settle in France, “whereas here assistants hardly look at them.”

But are these syndromes really specific to Jerusalem, Florence, or Paris? Do these cities merit a warning label of their own?

Mental health issues are among the leading causes of ill health among travellers. According to the World Health Organization, “psychiatric emergency” is one of the most common medical reasons for air evacuation. Specifically, acute psychosis accounts for up to a fifth of all mental health problems in travellers – and most of these aren’t standing in front of Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity or the Wailing Wall.

There are plenty of reasons weary travellers are tipped over the edge. Dehydration, insomnia, and jetlag have been implicated in travel psychosis, along with sleeping pills taken or alcohol consumed on a flight or, in some cases, drugs like the anti-malarial mefloquine. The prevalence of fear of flying ranges from 2.5% to 6.5%, and that of acute anxiety among travellers is about 60%. Add in the stress of airport security, long queues outside museums, language barriers and cultural differences, and then perhaps an intensely personal and long-anticipated religious or cultural pilgrimage, and the perfect storm is conjured up.

For many severe cases, it’s likely that travellers had an undiagnosed psychiatric condition or a predisposition to psychosis long before reaching Florence’s Uffizi or Galleria dell’Accademia. More than half of those admitted to hospital in Magherini’s study had previous contact with a psychiatrist of psychologist. And commentators in the British Journal of Psychiatry suggest that “Jerusalem should be not be regarded as a pathogenic factor, since the morbid ideation of the affected travellers started elsewhere”.

There’s even a caveat about Stendhal himself. His detailed contemporaneous diary of his 1817 visit to Florence was prosaic with complaints about his tight-fitting boots but there wasn’t a word of his intense experience at Santa Croce Basilica, even though his published travelogue claimed it was “the profoundest experience” and that he had “reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations”.

Could it be that proclaiming a swooning reaction to Renaissance art serves to assert one’s status, sophistication and superiority? Or should we believe that such splendour, rather than jet lag and long museum queues, can truly prompt a disintegration of the mind?

As one poet wrote nearly 100 years ago:

…for beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror,

which we can just barely endure,

and we stand in awe of it as it coolly disdains to destroy us. Every angel is terrifying.

Duino Elegies (1923)

The feature is written by Jules Montague

Recent Comments