The Cold War bunkers that cover a country

Fearing invasion during the Cold War, Albania’s leader Enver

Hoxha forced his country to build tens of thousands

of bunkers. Long after the regime’s collapse,

many still remain.

By Stephen Dowling in Albania

It is a spring morning and the sun is already high and hot. I am scrambling across the ruins of Orikum, a Roman-era settlement that lies at the southern end of the sweeping Bay of Vlore, on Albania’s Adriatic coast. It is a remarkably well-preserved memory of the Roman occupation, complete with a theatre that still retains many of its stone steps.

But it is not why I am here.

There is another ruin at the foot of Orikum’s crumbling structures, though this one is less than half a century old, and far less celebrated. It was once the barracks for the nearby Pasha Liman naval base, which can be seen on the other side of the causeway road.

My guide, Elton Caushi, jokes that we are ignoring a 2,000-year-old ruin in favour of a 40-year-old one.

Between the ruins of the naval barracks and the road are a handful of bunkers. They are squat and grey, just tall and wide enough to fit a pair of people in each. The walls are crowned with a rounded cupola. They have been here since the 1970s, when Albania was one of the most isolated countries on Earth.

You might also like:

The nuclear bunker in ‘Europe’s North Korea’

How the Cold War Vulcan bomber flew again

The monster atomic bomb too big to use

The bunkers were the brainchild of Enver Hoxha, a former partisan who ruled post-war Albania for 40 years under a regime both brutal and surreal. Convinced that everyone from neighbouring Yugoslavia to Greece, Nato and even his former allies in the Soviet Union wanted to invade his country, Hoxha embarked on a bunker-building programme of titanic proportions.

The bunkers gazing out across the Bay of Vlore are the tip of a concrete-and-steel iceberg. From the northern border with Montenegro to the beaches facing the Greek island of Corfu, Albania was covered with bunkers in a frenzy of paranoid construction. They were built not just in their hundreds, or even several thousand – a conservative estimate puts the number of completed bunkers at more than 170,000.

Today, they continue to litter the countryside, brooding over mountain valleys, silently guarding crossroads and highways, lined like unearthly statues on deserted beaches. Their legacy goes beyond the physical; each is thought to have cost the equivalent of a two-bedroom apartment, and their construction undoubtedly helped turn Albania into one of the poorest countries in Europe, a legacy which remains to this day.

Hoxha had a name for the state of preparedness all Albanians should be in – gjithmone gati, or “always ready”. This state of mind came in part from his experiences in World War Two.

Albania’s small, poorly equipped military had been crushed when Fascist Italy invaded in 1939; fighting officially ceased after just five days. But the resistance did not completely end; it just melted away.

Albania is a mountainous country, perfect for guerrilla warfare, and its people earned a reputation for fiercely resisting invaders over the centuries. As the war progressed an Albanian partisan movement, helped by comrades in occupied Yugoslavia and their British and Americans allies, began attacking the Italian and German occupiers. Foremost among the resistance movement were communist partisans, led by Hoxha.

As the tide swung the Allies’ way, the Albanian resistance grew, gathering strength in mountain hideouts that proved impossible to dislodge. By the time they liberated the capital Tirana in November 1944, this rag-tag army of communists and nationalists was some 70,000 strong.

After World War Two ended, Hoxha consolidated power, ruthlessly exterminating rival factions and even some of his fellow resistance leaders. It became a Soviet-aligned communist state. The small country then stumbled from one diplomatic crisis to another. In 1947 Hoxha broke off relations with neighbouring Yugoslavia, ostensibly because the less hard-line Yugoslavs were straying from the true path of socialism.

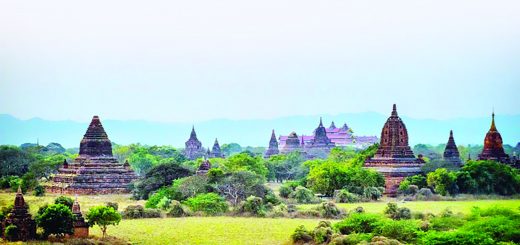

Albania would become a land covered in bunkers

Albania then lurched into another problem in 1961 after Hoxha declaimed Stalin’s reform-minded successor Nikita Khrushchev. The Soviets and the rest of the Warsaw Pact froze Albania out, forcing the isolated state to align itself instead with Mao Zedong’s China.

This honeymoon, too, was short-lived. Incensed by Mao’s welcoming of US president Richard Nixon to China in 1972, Hoxha rapidly cooled relations with the Chinese too. By 1978, the Chinese had withdrawn all their advisors, leaving Albania without allies – and the most isolated country in the world.

It was against this backdrop that the bunkerisation began. Hoxha’s hard-line socialism had made it vulnerable, he thought, to Nato attacks from Italy or neighbouring Greece. But he had also made enemies of former friends. An invasion could come from the Yugoslavs themselves, or their country could be used as a corridor for a Soviet invasion via Bulgaria.

Albania’s small armed forces would have been no match in a conventional battle against these much larger possible foes. Hoxha instead called on the mobilisation of the general populace – most of whom had to do basic military training each year – to form a resistance in their tens of thousands.

In the days of the partisans, this would have been conducted from mountain hideouts, where small units would carry out attacks on the Italian or German outposts on lower ground. But Hoxha wanted to make sure that any potential invader would be put off from mounting an assault in the first place by creating a vast network of bunkers. From here, the people of Albania would contest every beach, village and crossroads.

This national resistance would call for a monumental construction project. Albania would become a land covered in bunkers.

Even bigger bunkers were constructed to protect civilians in case of attack

The most numerous were the QZ (Qender Zjarri or “firing position”). Designed to hold only one or two people, they were built from reinforced concrete.

The designer of the QZ was Josif Zagali, an engineer who had been a partisan during World War Two. Zagali mounted a rounded cupola on the top of the bunker so that bullets and shell fragments would rebound off it, giving the QZ its distinctive shape. The QZs would be built in small groups that could defend each other. The parts were designed to be prefabricated in factories and then assembled on site.

Larger command/artillery bunkers, known as PZs (Pike Zjarri or “firing point”) were more than 8m (26ft) across. In wartime, these would act as command posts for rows of smaller QZs.

Even bigger bunkers were constructed to protect civilians in case of attack. Every town or city district would have underground concrete bunkers big enough to house hundreds of people. In 2016, on a previous trip to Albania, I visited one of the old shelters in Gjirokaster, a city of 25,000 some three hours’ drive south of Tirana. It was big enough to easily hold hundreds of people.

One of those in charge of the construction of Hoxha’s concrete defences was Pellumb Duraj, a commander in an engineering detachment based in Burell in the north of Albania.

He graduated as a civil engineer in 1973 and was one of the first engineers drafted straight into the army. “I was appointed there – I had no choice,” he tells me over coffee outside a Tirana cafe.

“There was a need for more added protection because Albania left the Warsaw Pact, and [we] were alone in our political outlook and we were scared of atomic bombs and the American threat, so that situation pushed the government to ask for the building of bunkers. That was starting in 1968 when we left the Warsaw Pact.

“The most intensive process was starting from 1975, so in these seven years we had to do the studies of the projects to pave the way to building the bunkers. Until then the army didn’t have civil engineers, they hired them from time to time.”

It was Duraj’s job to make sure the bunker’s parts were not only produced and transported to the right place, but also that there were enough people onsite to put them together. And that was no small task; the army division Duraj was assigned to had 13,000 bunkers of various sizes to build.

At the beginning we had no experience, so it was the start of a new challenge, a very difficult one – Pellumb Duraj

Constructing the bunkers was such a monumental task that almost every major factory in Albania was put to work. Cement factories churned out prefabricated concrete sections that an army of labourers would assemble in the field. With Chinese help, a huge new steelworks was built in 1974 to produce metal, much of it to reinforce Hoxha’s army of bunkers.

Duraj had to negotiate with the collectives who were in charge of the rural settlements, which were organised much like the collective farms in the USSR. “At the beginning we had no experience, so it was the start of a new challenge, a very difficult one. In a way we could say the whole nation was involved in this process. The military managed it, but the people did the work. Public construction companies would produce them, public transportation companies would transport them to the field and then we had to hire local people according to their skills. Then, the unskilled labour was done by soldiers.”

The small QZ bunkers were only the tip of the iceberg as far as Duraj’s responsibilities were concerned. “Besides the small bunkers, the firepoints, we had to also build positions for anti-aircraft guns and for artillery, and also the warehouses and storage for the ammunition, we had to build the trenches connecting all the storage buildings and the bunkers. We had to deal with all the communications between them. We dealt also with command points for all the military, tunnels or underground constructions. Ammunition storage was built by us, fuel deposits, food and clothing and chemical storages.

Even where the bunkers were to be located meant changes to their design, Duraj says. “In the western part, starting by the sea we built single-element bunkers that were heavy, they weighed about seven tonnes, because we were scared that an invasion would most likely come from the sea. They had a reinforced plate of iron that would protect it from missiles and bullets.

“In the mountains the bunkers were lighter because they were designed to be carried by mules and men, and the heaviest element would weigh 100kg. But to build a firepoint bunker of the mountain type would take 70 different elements. The we had to connect them with iron and cement.”

Every drop of sweat consumed by the fortifications is a drop of blood saved on the battlefield – Pellumb Duraj

The engineers like Duraj were carrying out a task with no comparison in the modern world. As inspiration, they looked at some of the huge fortifications built in Europe before and during World War Two, such as the Maginot Line, which the French constructed amid the fear of a German invasion in the 1930s. “We studied their experience but what we built wasn’t a fortification of a line, but the fortification of the whole country – from the coastline to the top of the mountain.”

Duraj says the bunker building took some 80% of the army’s resources during this period. Building bunkers was more important than growing food. The official party line, he says, was that “defence was considered the duty above all duties, while agriculture was considered to be a question for everybody.

“Enver Hoxha would say the fortification of the country is the most efficient investment of our nation’s sweat, and every drop of sweat consumed by the fortifications is a drop of blood saved on the battlefield.”

The work had to be carried out in all weathers, the heaviest parts hauled up by tractors or by World War Two-era Soviet Zil trucks and then assembled by hand. “In good weather we could do up to four bunkers a day,” Duraj says, “but in poor conditions… sometimes we’d see the Zil trucks stuck in mud up to the chassis, and then we had to get a tractor to pull the truck out. We also had accidents with cranes falling, killing people accidentally.”

In places that even goats wouldn’t pass, we had to build bunkers – Pellumb Duraj

The BunkArt museum in Tirana estimated that the bunker building programme cost 100 lives for every year of construction. Duraj claims those numbers are too high, but agrees that there were fatal accidents during the construction of the bunkers.

More than 25 years after the fall of the communist regime, Duraj has had plenty of time to consider the strategic worth of Hoxha’s bunker defences. Was Albania really under such grave threat that it needed to build this many? “If you ask me, it was exaggerated. We built bunkers in mountaintops, on the rocks. In places that even goats wouldn’t pass, we had to build bunkers.”

***

The bunkers were born in factories like one my guide Caushi and I visit in Gjirokaster.

This would have once been a hive of industry, as concrete cupolas were produced around the clock, ready to crown the tops of waiting bunkers. Today it is just a shell. The factory was torn down long ago, leaving little except rubble and the overhead gantries that would once have hauled heavy concrete slabs across the factory. It is a picture of post-communist decay.

Near the ruined factory is Adi, who runs a local scrapyard, full of dystopian piles of crushed metal and soot-faced workers burning plastic off wires. When he bought the property, he also inherited the old factory nearby. It’s somewhat ironic – one of Adi’s jobs is to dismantle the bunkers.

He and his workers sometimes travel into the mountains that loom over Gjirokaster, four hours’ drive away. It can take 10 of them a whole day to dismantle a bunker. They travel by car – when the construction brigades had to build them, it was often done with little more than the help of mules.

The 38-year-old Adi remembers the bunkers from when he was a boy. “We’d play on them, play partisans vs Germans. Now we find the reminders of those days and thank God we had no war.”

Albanians have turned these silent reminders of the country’s communist past to a variety of uses

One of Adi’s workers, Nico, also remembers travelling up to the mountains with his friends and playing in the bunkers, long after the communist regime that built them had faded into history. By then the bunkers had been colonised by snakes, though Nico is convinced that one day he will find one full of treasure.

‘Treasure’ of a different sort turned up in one bunker in 2004. Some 16 tons of mustard gas canisters were found in a bunker only 40km from Tirana – the US had to pay the Albanian government some $20m to safely dispose of the weapons.

While the likes of Adi are breaking up the bunkers to use the metal and concrete in modern construction projects, Albania doesn’t have the money – or the manpower – to remove them en masse. The QZs and PZs, instead, linger like the remains of some long-vanquished army.

Albanians have turned these silent reminders of the country’s communist past to a variety of uses. In rural areas, they have been turned into animal shelters or are used for feed storage. Others, brightly painted, have become parts of inner-city playgrounds. The bunkers that once guarded Albania’s sun-drenched coastline have, in some cases, been turned into pizzerias, espresso bars and makeshift bars, though many have also been removed – often using retired tanks as towing vehicles – to make way for new developments.

But they are already attracting foreigners, both tourists and artists, compelled to capture them for posterity.

David Galjaard is a Dutch photographer who has travelled several times to Albania to shoot the bunkers.

“I was working on a series about Cold War bunkers in the Netherlands, when a journalist of the paper we both worked for (NRC Handelsblad) said to me: ‘Hey! If you like bunkers so much, you should go to Albania’,” Galjaard tells me over email. “When I read about the bunkers, and their history I couldn’t wait to go. It was December at that time. So, I waited until the snow melted (in Albania) and got into my Peugeot.

“Before I arrived in Albania for the first time, I imagined a country that was full of scars. I felt sorry for the Albanians that they had this constant reminder of the harsh communist period. But when I arrived and asked about them, people shrugged. They often had no problems with it, unless the bunkers, for example, got in the way when ploughing their fields.”

Galjaard’s three trips to Albania became the photo project Concresco, which was published as a book in 2012.

“The way that the Albanian people deal with the bunkers says a lot about the country,” says Galjaard. “The way that they are ignored, or used for another purpose, or destroyed. This is why I used them as a visual metaphor to not only tell a story about the bunkers, but about the country itself.

There’s been a huge process of demolishing and getting rid of them – Elton Caushi

“In most countries, large parts of the vestiges of the Cold War were never visible for most people. What’s unique about Albania is that the paranoia and xenophobia from that time always was and is still so clearly visible.”

Caushi makes his living, partly, by presenting these relics of the Cold War as part of Albania’s uniqueness. He runs a tourism company, Albanian Trips, that includes visits to some of the most scenic reminders of Hoxha’s paranoia – mixing the country’s rugged, mountainous splendour with stark reminders of its decades of isolation.

“Me and my photographer Swiss friend Didier Ruef took a three-week trip around Albania, chasing bunkers,” Caushi says. “We did find several ones being used as houses, animal houses but also plenty being beautifully located near beach or mountain views. Didier had already told me that he thought Albania would become a great tourist destination one day and that bunkers would have played a role in that. But I probably paid little attention to that.

“Then the idea became more and more clear after I really focused into travel and tourism, starting around 2007, full time. People didn’t stop asking about them. I started meeting constructers, authors, recyclers, demolishers, scrap gatherers and amount of info started to become more and more important.”

I hate and love them at the same time – Elton Caushi

Caushi and I spend a couple of days travelling across the country, finding clusters of bunkers on the roads from Tirana down to Gjirokaster. In the past decade he has built up a map of the most photogenic examples. But little by little Hoxha’s bunkers are disappearing.

“(There are) not many left if compared to 15 years ago,” he says. “There’s been a huge process of demolishing and getting rid of them. For scrap and because they occupy land.

“I believe maybe 45-50% disappeared between 2006 to 2014. Then the government said they’re public property and whoever damages them will be persecuted by the Albanian law.” Despite being protected, Caushi believes many more will be destroyed over the coming decade.

He often takes tourists to the bunkers that sit inside Tirana’s main cemetery. Here they seem to blend in amongst the tombs and gravestones. Others can be reached only by boat. Then there are the tunnels, the underground caverns and storage areas forgotten after the Cold War, now being rediscovered as tourism opens up the country.

“There’s a huge one in a location which I will not tell: filled with a colony of thousands of bats. Quite odd to go inside. You walk on a thick layer of bat excrement and they fly all around your head and sometimes come touch your hair. While at all entrances you’re surrounded by slogans relating to Stalinist propaganda and technical advice on how to shoot at the enemy that will one day try to invade us!”

Caushi, who left Albania in the 1990s to study in Switzerland before returning some years later, has mixed feelings about Hoxha’s enduring legacy. “I hate and love them at the same time. They’re odd and if I would have had any power to stop them from happening I would have certainly done so. But since they’re here and we did pay with so much sacrifice for their construction, I believe the best way to punish who forced us to pay and work for making them, is to recycle them into things that satirise the original project: keep the enemy away. Let’s try to attract the ‘enemy’ into them.

“It’s a tragicomic approach and I believe it’s healthy. From the original barrier that they should have eventually been, they can become shelters for the ‘enemy’ to come, have fun, explore and learn from them. Learn from this huge mistake and try not to let it happen again in the future.”

For those who built them, the bunkers perhaps represent the years lost to Hoxha’s paranoia. When visiting the derelict factory in Gjirokaster, Caushi begins talking to a group of workmen building a wall nearby. One of the workmen, Isa, tells him that the iron mould used to cast the bunker cupolas is now a water tank in the garden of his sister’s neighbour. He invites us to come up and take a picture of it.

Over a glass of homemade raki, he and his brother-in-law tell us of the summers they built bunkers back in their army days, lugging 40kg slabs of concrete up trails to build bunkers which never fired a shot in anger.

“While the rest of the world was building rockets to send men to the Moon, we were building bunkers,” his brother-in-law snorts. “Madness.”

Recent Comments