What Is 5G?

Verizon Wireless has won the race to 5G—sort of. On October 1, Verizon launched its “5G” home service in Houston, Indianapolis, Los Angeles and Sacramento, establishing equivocal bragging rights and setting off a domino run of 5G network launches that will continue through next spring.

That first network isn’t actually the real, global mobile standard for 5G. The first one of those will likely be AT&T’s network, coming by the end of the year. (Verizon plans to switch to the global standard next year, swapping out equipment at no cost to existing customers.) This all means you’re about to see the marketing for 5G get ramped up quite a lot, and so it’s good to know what everyone’s actually talking about.

5G stands for fifth-generation cellular wireless, and the initial standards for it were set at the end of 2017. But a standard doesn’t mean that all 5G will work the same—or that we even know what applications 5G will enable. There will be slow but responsive 5G, and fast 5G with limited coverage. Let us take you down the 5G rabbit hole to give you a picture of what the upcoming 5G world will be like.

1G, 2G, 3G, 4G, 5G

1G, 2G, 3G, 4G, 5G

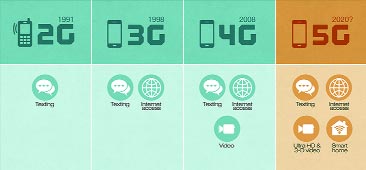

The G in 5G means it’s a generation of wireless technology. While most generations have technically been defined by their data transmission speeds, each has also been marked by a break in encoding methods, or “air interfaces,” which make it incompatible with the previous generation.

1G was analog cellular. 2G technologies, such as CDMA, GSM, and TDMA, were the first generation of digital cellular technologies. 3G technologies, such as EVDO, HSPA, and UMTS, brought speeds from 200kbps to a few megabits per second. 4G technologies, such as WiMAX and LTE, were the next incompatible leap forward, and they are now scaling up to hundreds of megabits and even gigabit-level speeds.

5G brings three new aspects to the table: greater speed (to move more data), lower latency (to be more responsive), and the ability to connect a lot more devices at once (for sensors and smart devices).

The actual 5G radio system, known as 5G-NR, won’t be compatible with 4G. But all 5G devices, initially, will need 4G because they’ll lean on it to make initial connections before trading up to 5G where it’s available.

4G will continue to improve with time, as well. The upcoming Qualcomm X24 modem will support 4G speeds up to 2Gbps. The real advantages of 5G will come in massive capacity and low latency, beyond the levels 4G technologies can achieve.

That symbiosis between 4G and 5G has caused AT&T to get a little overenthusiastic about its 4G network. The carrier has started to call its 4G network “5G Evolution,” because it sees improving 4G as a major step to 5G. It’s right, of course. But the phrasing is designed to confuse less-informed consumers into thinking 5G Evolution is 5G, when it isn’t.

Verizon’s home service, which is a nonstandard form of 5G, has led its competitors to claim that it’s not really 5G. But given that it offers multi-gigabit wireless speeds and will be swiftly transitioned over to the standard version, I’m willing to give Verizon a pass.

How 5G Works?

How 5G Works?

Like other cellular networks, 5G networks use a system of cell sites that divide their territory into sectors and send encoded data through radio waves. Each cell site must be connected to a network backbone, whether through a wired or wireless backhaul connection.

5G networks will use a type of encoding called OFDM, which is similar to the encoding that 4G LTE uses. The air interface will be designed for much lower latency and greater flexibility than LTE, though.

5G networks need to be much smarter than previous systems, as they’re juggling many more, smaller cells that can change size and shape. But even with existing macro cells, Qualcomm says 5G will be able to boost capacity by four times over current systems by leveraging wider bandwidths and advanced antenna technologies.

The goal is to have far higher speeds available, and far higher capacity per sector, at far lower latency than 4G. The standards bodies involved are aiming at 20Gbps speeds and 1ms latency, at which point very interesting things begin to happen.

What’s the Frequency?

5G primarily runs in two kinds of airwaves: below and above 6GHz.

Low-frequency 5G networks, which use existing cellular and Wi-Fi bands, take advantage of more flexible encoding and bigger channel sizes to achieve speeds 25-50% better than LTE, according to a presentation by T-Mobile exec Karri Kuoppamaki. Those networks can cover the same distances as existing cellular networks and generally won’t need additional cell sites. Sprint, for example, is setting up all of its new 4G cell sites as 5G-ready, and it’ll just flip the switch when the rest of its network is prepared.

The real 5G innovation is happening at higher frequencies, known as millimeter wave. Down in the existing cellular bands, only relatively narrow channels are available because that spectrum is so busy and heavily used. But up at 28Ghz and 39Ghz, there are big, broad swathes of spectrum available to create big channels for very high speeds.

Those bands have been used before for backhaul, connecting base stations to remote Internet links. But they haven’t been used for consumer devices before, because the handheld processing power and miniaturized antennas weren’t available. Millimeter wave signals also drop off faster with distance than lower-frequency signals do, and the massive amount of data they transfer will require more connections to the landline Internet. So cellular providers will have to install more, smaller, lower-power base stations rather than use existing powerful macrocells to offer the multi-gigabit speeds that millimeter wave networks promise.

Who’s Launching 5G When?

AT&T has proclaimed that it will be first with mobile 5G when it launches a network in 19 cities by the end of this year. The company has listed its 19 citiesand says that initially there will be one 5G device, a mobile Internet hotspot that we think will be a version of the Netgear Nighthawk M1. Phones will come next year. AT&T will use 38Ghz spectrum for its initial rollout.

Verizon is starting out with its fixed 5G home internet service, which is now available. It will follow with a mobile 5G network in 2019, the carrier has said. Verizon’s first 5G phone could be the Moto Z3, which has a 5G add-on promised for early next year. The carrier is mostly using 28Ghz spectrum.

5G home internet shows one major advantage over 4G: huge capacity. Carriers can’t offer competitively priced 4G home internet because there just isn’t enough capacity on 4G cell sites for the 190GB of monthly usage most homes now expect. This could really increase home internet competition in the US, where, according to a 2016 FCC report, 51 percent of Americans only have one option for 25Mbps or higher home internet service. For its part, Verizon said its 5G service would be truly unlimited.

5G home internet is also much easier for carriers to roll out than house-by-house fiber optic lines. Rather than digging up every street, carriers just have to install fiber optics to a cell site every few blocks, and then give customers wireless modems. Verizon chief network officer Nicki Palmer said the home Internet service would eventually be offered wherever Verizon has 5G wireless, which will give it much broader coverage than the carrier’s fiber-optic FiOS service.

T-Mobile is building a nationwide 5G network on the 600MHz and 28Ghz bands starting in 2019, with full national coverage by 2020.

The speed of a wireless network is tied to how much spectrum you can use for it. Because T-Mobile is only using an average of 31MHz of spectrum at 600MHz as opposed to the hundreds of MHz that millimeter wave networks will use, its low-band 5G network will be a little bit faster than 4G, but not multiple gigabits fast. It will still have the low latency and many connections aspects of 5G, making it usable for gaming, self-driving cars, and smart cities, for instance. In cities, the millimeter-wave network will be super fast.

“Are we going to see average speeds start to move up by tens of megabits per second? For sure,” T-Mobile CTO Neville Ray said. “We would love to see average speeds triple, or move to 100Mbps, but that’s a journey that’s going to take time in the industry.”

Sprint announced its first 5G phone in August, saying an integrated 4G/5G Android phone from LG will come to its network during the “first half of 2019.” Sprint’s 5G will be on the 2.5GHz band, which will give it similar coverage to Sprint’s existing 4G LTE network; in fact, it will use the same cell sites. Sprint CTO John Saw said that means its 5G phones will be slimmer and slicker than 5G phones which use the new 28Ghz bands.

Phone company OnePlus has committed to releasing a 5G phone in 2019, although it hasn’t said what network it will be for. So far, Apple and Samsung haven’t made any solid commitments to 5G phones for the U.S. We think there will be a 5G iPhone in 2020.

What’s 5G For?

So Verizon wants to initially use 5G as a home internet service, and everybody else is more focused on faster smartphones. Those uses are table stakes, just to get the networks built so more interesting applications can develop in the future.

On a trip to Oulu, Finland, where they have a 5G development center, we attended a 5G hackathon (see the video above). The top ideas included a game streaming service; a way to do stroke rehab through VR; smart bandages that track your healing; and a way for parents to interact with babies who are stuck in incubators. All of these ideas need either the high bandwidth, low latency, or low-power-low-cost aspects of 5G.

This year, we surveyed the 5G startups that Verizon is nurturing in New York. At the carrier’s Open Innovation Lab, we saw high-resolution wireless surveillance cameras, game streaming, and virtual reality physical therapy.

Our columnist Michael Miller thinks that 5G will be most important for industrial uses, like automating seaports and industrial robots.

Driverless cars may need 5G to really kick into action, our editor Oliver Rist explained after CES this year. The first generation of driverless cars will be self-contained, but future generations will interact with other cars and smart roads to improve safety and manage traffic. Basically, everything on the road will be talking to everything else.

To do this, you need extremely low latencies. While the cars are all exchanging very small packets of information, they need to do so almost instantly. That’s where 5G’s sub-one-millisecond latency comes into play, when a packet of data shoots directly between two cars, or bounces from a car to a small cell on a lamppost to another car. (One light-millisecond is about 186 miles, so most of that 1ms latency is still processing time.)

Another aspect of 5G is that it will connect many more devices. Right now, 4G modules are expensive, power-consuming, and demand complicated service plans, so much of the Internet of Things has stuck with Wi-Fi and other home technologies for consumers, or 2G for businesses. 5G networks will accept small, inexpensive, low-power devices, so it’ll connect a lot of smaller objects and different kinds of ambient sensors to the internet.

What about phones? The biggest change 5G may bring is in virtual and augmented reality. As phones transform into devices meant to be used with VR headsets, the very low latency and consistent speeds of 5G will give you an internet-augmented world, if and when you want it. The small cell aspects of 5G may also help with in-building coverage, as it encourages every home router to become a cell site.

We’re looking forward to testing the first implementations of 5G as soon as they are live. Every year we drive around the country evaluating network speeds for our Fastest Mobile Networks feature, and as 5G rolls out, the results are sure to get more interesting—and exciting—than ever before.

Recent Comments