Mosque of Whirling Colours

There are numerous mosques all around the world. Each has a design of its own. However, in order to be distinctive from other mosques, a mosque needs to be unique and possess outstanding features. One such mosque is The Nas?r al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz, Iran. From outside it looks like a conventional mosque, but inside there is something more…

There are numerous mosques all around the world. Each has a design of its own. However, in order to be distinctive from other mosques, a mosque needs to be unique and possess outstanding features. One such mosque is The Nas?r al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz, Iran. From outside it looks like a conventional mosque, but inside there is something more…

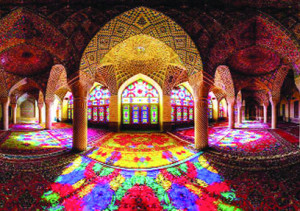

The mosque is called by many different names. Mostly known as the “Pink Mosque”, it is also called the “Mosque of colours,” the “Rainbow Mosque” or the “Kaleidoscope Mosque”. This is a space where light and worship intertwine. The mosque comes to life with the sunrise and colours dance throughout the day like whirling dervishes. It reflects on the ground, walls, the arches and the towering spires. It even reflects on the visitors as if a colourful ball is hit by the first sun ray and explodes to thousands of butterflies all around.

The original name of the mosque in Persian is Masjed-e Naseer ol Molk. Wikipedia mentions it as an ordinary Iranian mosque; however, the interior hides an impressive piece of architecture and design.

Built by the order from one of the lords of the Qajar Dynasty, Mirza Hasan ‘Ali Nasir al-Mulk, it took 12 years to complete in 1888. Its interior reveals a magnificent masterpiece of design with stunning colours.

The designers Muhammad Hasan-e-Memar and Muhammad Reza Kashi Paz-e-Shirazi used extensivelystained glass on the façade and other traditional elements such as panj k?seh-i (five concaves), which create a breath taking effect of the interior like standing in a kaleidoscope. Once the sunlight hits the stained glass, the entire building is flooded by a vibrant rainbow of colours. In popular culture, the mosque is also called Pink Mosque, because its tiles are beautifully decorated with a pre-eminently pinkish rose colour.

Don’t miss out the 360 degrees intreactive image below. Please grab it with a click of your mouse and move it around:

Today this gorgeous mosque is still in use under protection by Nasir al Mulk’s Endowment Foundation. Built in late 19th century, not very new and not very old, it is a celebration of both classic and modern times embedded in Islamic heritage. Speaking of this heritage, it has roots in Islamic art, architecture, tile making, geometry, patterns and other arts that flourished in the Golden Age of Islam. For example the “New Discoveries in the Islamic Complex of Mathematics, Architecture and Art” article, written by the president of FSTC, Professor Salim Al-Hassani, shows a very interesting link with patterns on the mosques and a sophisticated geometry, where art enterwined with science.

The production of coloured glass in west Asia existed around the 8th century, at which time the scholar nicknamed the father of chemistry J?bir ibn Hayy?n wrote his book Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna (The Hidden Pearl). In it he gave 46 recipes for producing coloured glass and described the technique of cutting glass into artificial gemstones. There is more information on this in From Alchemy to Chemistry or The Advent of Scientific Chemistry.

The artistry of these colours can be seen throughout Middle East and Anatolia (minor Asia), for example Iznik tiles or Kütahya ceramics in Turkey. It is no surprise because once Iran was under Ottoman rule and the Turks came from central Asia through Persia and had Turkish dynasties around that area like Seljuks, Khwarazmian, Ghaznavids and many others way before Ottomans. It is also connected to Europe, about which Richard Covington wrote in his “East Meets West in Venice” article: “A similar give-and-take process occurred in glass production. Recognizing that the glassmakers of Syria and Egypt had no serious rivals in Europe, the Venetians began importing raw glass, as well as broken glass (cullet) and plant soda ash from the Levant around the 13th century to copy Muslim designs at home. So successful was the transfer that certain enameled and gilt beakers, decorated with camels and desert plants and once believed to have originated in Syria, turned out to be Venetian-made. By the middle of the 15th century, Venetian glassmakers had perfected a technique to produce cristallo glass, a clear, colorless creation, free of defects, that successfully imitated expensive rock crystal. Ottoman artisans soon adapted the technique in the manufacture of Iznik porcelain. Thus a process that had begun with Venetians borrowing styles and materials from Islamic craftsmen came full circle with Ottoman ceramists building on Venetian expertise.” From this shared history beautiful masterpieces came out by mastering colours on ceramics, tiles, glasses, and through these elements especially on and in mosques.

When looking at the photos of the interior of Nas?r al-Mulk Mosque one might think they are 3D images made by professional software. One might not be wrong, if one sees some 3D works inspired by the mosque itself. For example Barbara Witkowska shows modelling tutorial process of Evermotion collection – Archinteriors vol. 31. – Making of Nasir al-Mulk Mosque. One might not distinguish between real and animated image. To that point even one of the visitors to the mosque said “it is a mosque from a fairyland”.

Japanese photographer Koach was blown away by the mosque’s beauty which is best appreciated in the morning light, explaining: “You can only see the light through the stained glass in the early morning. It was built to catch the morning sun, so that if you visit at noon it will be too late to catch the light. The sight of the morning sunlight shining through the colorful stained glass, then falling over the tightly woven Persion carpet, is so bewitching that it seems to be from another world.

Even if you are the world’s least religious person, you might feel your hands coming together in prayer naturally when you see the brilliance of this light. Perhaps the builders of this mosque wanted to show their “faith” through the morning light shining through this stained glass.”

Recent Comments