Keeping The Space Station Clean

By 1998, after 12 years in orbit, Russian space station Mir was showing its age. Power cuts were frequent, the computers unreliable and the climate control system was leaking. But when the crew began a study to assess the types of microbes they were sharing their living space with, even they were surprised at what they found.

Opening an inspection panel, they discovered several globules of murky water – each around the size of a football. Later analysis revealed the water was teeming with bacteria, fungi and mites. Even more concerning were the colonies of organisms attacking the rubberised seals around the space station windows and the acid-excreting bugs slowly eating the electrical cabling.

When each Mir module launched from Earth it was near-pristine, assembled in clean rooms by engineers wearing masks and protective clothing. All the unwanted life now living on the station had been carried into orbit by the multinational group of men and women who subsequently occupied the orbiting laboratory.

We share our lives, and bodies, with microbes. From the bacteria lining our gut, to the microscopic mites nibbling at our dead skin, it’s estimated that more than half the cells in our body aren’t human. Most of these microbes are not only harmless but essential, enabling us to digest food and fend off disease. Everywhere we go, we take our

microbiome with us and – just like humans – it’s learning to adapt to life in space.

“Space is a very stressful environment, and not just for humans,” says Christine Moissl-Eichinger, who’s led a recent European Space Agency (Esa) study into the International Space Station’s (ISS) microbiome using samples collected by the astronauts and cosmonauts on board. “Spaceflight causes stress for crewmembers and we wondered if the microbes would be stressed as well and react in a bad way.”

Her research is timely. By November this year, the ISS will have been occupied continuously for 20 years. After the experience of Mir, biologists have been concerned about what else might be living on board and particularly any microbes that might endanger the station, or worse, the astronauts.

“We expected to see differences in the genetic make-up or the composition of the microbial community, due to the adaptations they must have gone through,” says Moissl-Eichinger from the Medical University of Graz in Austria.

The scientists found that the ISS has developed a stable population of some 55 different types of microorganisms. But, despite the lack of gravity, these bacteria, fungi, moulds, protozoa and viruses have adapted well to their surroundings.

“They weren’t more resistant to antibiotics or had other potentially harmful traits for the humans,” says Moissl-Eichinger. “But we did find they had adapted to all the metal surfaces.”

These metal munching microbes are known as technophiles and, as with Mir, could pose a long-term risk to space station systems. “In the long run, this might result in difficulties with the proper and safe management of the space station.”

It’s up to the crew to help keep the ISS microbiome population under control. Every week astronauts are scheduled to wipe down surfaces with antimicrobial wipes and use a vacuum cleaner to suck-up any stray debris. This is on top of daily housekeeping to keep kitchen areas clean and prevent sweaty exercise gear and equipment from going mouldy.

“We rely partially on the astronauts to do the housekeeping,” says Christophe Lasseur, who heads research into life support systems at Esa. “But we also rely on technology to filter the air and keep the water clean.”

Lessons learned on Mir have been applied to the design and operation of the ISS. The environment is drier (life loves water) and there is much greater movement of air, with a constant breeze blowing any dust towards a filter system.

“The main difference between being at home and on the ISS is that dust won’t settle but accumulates on the air vents,” says Lasseur. “But also any other object – like a pencil or pair of glasses – will be blown towards the air filter.” In fact, anything not attached to the walls has a tendency to migrate.

The experience on the ISS has shown that humans can coexist with their microbiome with few ill-effects. What concerns scientists now is what happens when we leave the relative safety of low Earth orbit to travel to the Moon and Mars.

“Today the space station is below the Van Allen radiation belts, so the exposure to radiation is reduced,” says Lasseur. “When we pass the Van Allen Belts then the exposure to radiation is going to be stronger and maybe the evolution of the microorganisms [through genetic mutation] will be a bit faster.”

Nasa is currently developing the next space station, a Moon-orbiting laboratory known as Gateway, where astronauts will live for several weeks. But then, potentially, they will leave it empty for months at a time.

“We have to be sure that when astronauts quit and come back, they don’t leave conditions that favour microbial growth,” Lasseur says, “because that could be serious.”

Effort is also going into considering what happens when we take our microbiome with us on the first human expeditions to the surface of Mars.

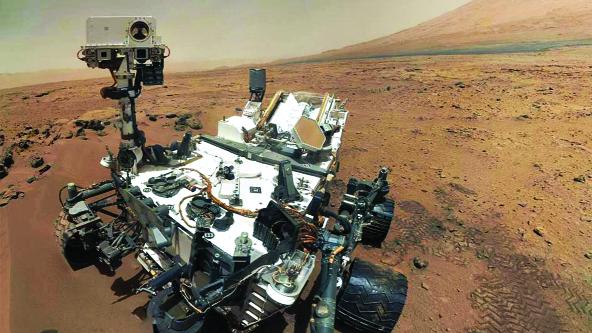

Everything we currently send to the Red Planet is meticulously clean. Esa’s latest Mars rover, for instance, was assembled in one of the cleanest rooms in the UK by engineers wearing special underwear, full-body suits, facemasks and two pairs of gloves. Due for launch later this year, the ExoMars rover is designed to look for signs of past or present Martian life. It is therefore vital that it’s not contaminated with any life from Earth.

But when humans go to Mars, they will be anything but clean. Removing all trace of existing microbial life from astronauts would be impossible, and probably fatal. So how do we stop ourselves from contaminating a pristine environment or mistaking Martian bugs for ones we have brought with us from Earth?

“Yes, we have a lot of microbes on our body, but we’re not going to be running around Mars naked,” says Esa’s planetary protection officer, Gerhard Kminek. “Astronauts will be wearing spacesuits to keep them alive and that will keep any contamination inside.”

The challenge will be to keep any human microbes covering the outside of the spacesuits from contaminating the Martian environment. It’s one of the issues being addressed by a working group from the world’s major space agencies, which is due to publish its recommendations on protecting Mars from the effects of human exploration later this year.

Of far more immediate concern, however, is the issue of bringing any Martian microbes back to Earth. A mission to return samples of Martian soil and rock is currently under development and there is a chance those samples could contain life.

From Andromeda Strain to The Thing, if science fiction has taught us anything it’s to be careful about bringing back space bugs to infect the Earth. And while this latest research shows there is nothing dangerous growing on the ISS, understanding the evolution of the microbiome on the station will help ensure the safety of the first astronauts to return from Mars.

“When the astronauts come back from Mars, if we see something in their microbiome, we can assess if this is something induced by potential Martian biology or whether it’s something that we have seen before in human spaceflight,” says Kminek, ominously.

In the meantime, microbiologists have something else to look forward to. There are some 96 bags of human waste on the Moon, left behind 50 years ago by the Apollo astronauts. When people return to the Moon within the next decade, Nasa hopes to recover some of these bags to discover whether any bacteria are still alive. If they are, it’ll mark another small step in our understanding of the human microbiome.

Recent Comments